Simulation of Human Body Kinematics

Roman Filkorn, Marek Kocan

filkorn@decef.elf.stuba.sk, marek_kocan@yahoo.com

Department of Computer Science and Engineering

Slovak University of Technology

Bratislava / Slovak Republic

Abstract

This paper describes experimental systems for modeling human body skeleton. System treats forward and inverse kinematics, problems of geometric transformations and the human body representation. We introduced various approaches and algorithms, which are analyzed and also implemented in an experimental application. We have experienced with modeling skeleton with VRML (geometry, appearance and script nodes, sensors, event modelling ), Java and JavaScript.

Keywords:

telepresence, VRML, Java, joint, event, node, inverse kinematics, forward kinematics, geometric transformation, quaternions, skeleton, human body, coordinate systems, keyframing.1. Introduction

Communications with audiovisual Avatars is one of the challenging tasks in Internet applications. This form of communication can be used in applications such as tele-education, tele-maintanance, training, electronic commerce etc. All these tasks require human body modeling. The work described in this paper is part of the larger project with the final goal to create system for non-verbal communication via Internet [1], [2].

Creating a synthetic human is a complex task, including skeleton, muscles, skin, hair and inner organs modeling, walking, gestures and face expressions capturing and modeling. The bones are solid but muscles change their shape. The animation of synthetic tissue, which is subject to force-based deformations through the action of contractible muscles such as wrinkling is quite time consuming computing.

Human body kinematics simulation is used in realistic human computer animated films, robotics, ergonomics analysis in industrial design (cars, airplane cockpit design), communities in distributed virtual environments (Avatars), language-training applications (together with face animation and voice synthesis), animated conversational agents in interpreting sign language.

2. Human skeleton modeling

Human skeleton modeling includes a wide range of problems to solve, human body representation, kinematics and dynamics. Kinematics is a science of movement without focusing on forces, which affect the movement. Kinematics is divided into direct (forward) and inverse kinematics. Forward kinematics gets position and orientation of last segment in a kinematics chain by defining angles for every join. On the other hand, inverse kinematics computes joint angles of a kinematics chain based on the position and orientation of last kinematics segment.

Dynamics considerate physical laws and uses various forces and kinetic energy that can vary with the time. Also dynamics is divided into forward and inverse dynamics. Forward dynamics explicitly sets forces and kinetic energy (varying in time) to the body segments. Then the movement is approximated in discrete time steps in which the values of forces and kinetic energy are known. Inverse dynamics deals with determination of forces and kinetic energy that are needed to reach the given goal. (This paper does not considerate dynamics at all).

The kinematics deals with rotations. We introduced two different approaches to solve rotations in 3D space - rotation matrices and quaternions (will be described later).

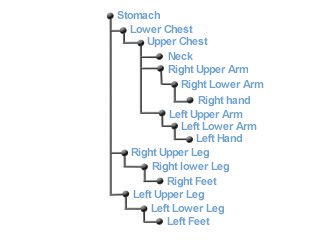

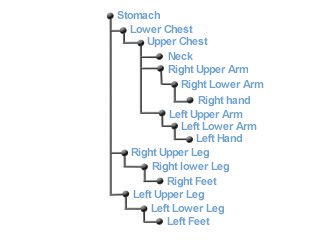

Figure 2.1: Human skeleton and the corresponding hierarchical structure

To model human body we need to select an appropriate representation. Human body consists of bones and joints that form a hierarchical structure - tree. Because human body is very complex, we decided to use simplified model of skeleton. Skeleton can be represented as a set of simply objects connected with joints. The complexity of the skeleton is given by degrees of freedom (DOF) where one DOF is represented by one rotational axis. So we can easily get with a detailed approximation more than 200 DOF. One possible simplified human body model and the corresponding tree structure is shown in figure 2.1. As seen from these figures, transformation created in one joint affects (is spread to) all child bones and joints.

2.1 Coordinate systems

The most common coordinate system is Cartesian coordinate system. It is used in a majority of applications and 3D APIs. But there exist more coordinate systems [3] that are not so popular but they can be more suitable for some kind of applications. So we can find to the Cartesian coordinate system following coordinate systems:

The most perspective system for application in human body modeling is a spherical coordinate system. The system consists of two angles that can represent a rotation angle about two rotation axis’s and a size parameter that can represent the size of the appropriate bone.

2.2 Direct kinematics

As mentioned above, direct kinematics explicitly sets rotations in joints (local transformations). Then the position and orientation of the last segment in a kinematics chain is given by the chain configuration. Global transformation (transforming the whole body) is given by transforming the root of the body structure. There occurs one basic geometric transformation – rotation. We introduced two different solutions for rotation. Both methods have their own advantages.

The first is rotation with rotation matrix. We used Rodriguez rotation matrix

where [ux, uy, uz] is the rotation axis and Y is the angle of rotation. The size of rotation vertex must be equal to one. Otherwise, at first the vertex has to be normalized. This matrix is easy to compute and also the rotation computational complexity is affordable.

The second method is usage of quaternions[7,8,9]. Because quaternions are not so popular I will describe them more detailed. Quaternion can be understood as an extension to complex numbers where instead of two components we have four, one real component and three imaginary components. Quaternion is a sequence of four numbers a b c d that are written as follows (a,b,c,d). We can also use directional vectors i, j, k to type a quaternion. Then the quaternion is described: a + bi + cj + dk. Quaternions are mostly denoted as ![]() . On quaternion are defined operations like scalar multiplication, size of a quaternion, quaternion conjugation, addition, dot product, quaternion multiplication, inverse quaternion etc... Quaternions naturally represent rotations. The quaternion that represents rotation around axis u by angle Y

is defined

. On quaternion are defined operations like scalar multiplication, size of a quaternion, quaternion conjugation, addition, dot product, quaternion multiplication, inverse quaternion etc... Quaternions naturally represent rotations. The quaternion that represents rotation around axis u by angle Y

is defined

![]() (2).

(2).

The rotation of a point p is then given by quaternion multiplication

![]() (3)

(3)

where![]() . Quaternion rotation can be simplified by using unit quaternions. Figure 2.2 shows the representation of quaternion.

. Quaternion rotation can be simplified by using unit quaternions. Figure 2.2 shows the representation of quaternion.

![]()

Figure 2.2: Quaternions q and –q represent the same rotation and inverse quaternion q –1 represents the opposite rotation

One of the quaternion advantages is the transformation composition (4).

(4)

(4)

Transformation composition is very often used by human body manipulation because the transformations influence the child joints and bones. Quaternion can be with advantage used to represent the state of a joint. This is because there exist an easy way how to get the rotation axis and rotation angle back from the quaternion.

2.3 Inverse kinematics

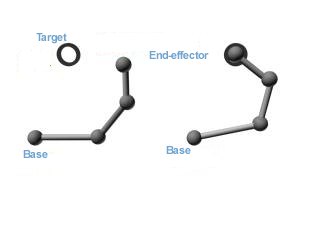

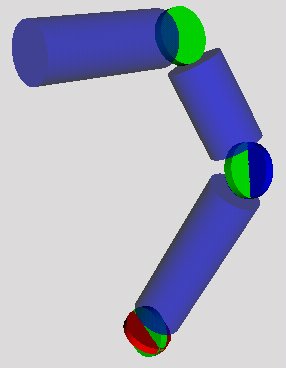

Inverse kinematics is based on an opposite approach as direct kinematics. Inverse kinematics uses a kinematics chain. Kinematics chain is a sequence of segments and joints. The first joint is a base and the last is a end-effector as shown in figure 2.3. Base joint is an anchor that it is not moved. End-effector is the joint with them we move. The position and orientation of every joint based on end-effector movement is changing. The deal of inverse kinematics is to compute the changed positions and orientations.

Figure 2.3: Kinematics chain

Inverse kinematics offers three ways how to get the solution. Possible methods are algebraic, geometric and iterative. Algebraic and geometric methods provide an exact solution (and if there exist more solutions then the methods will give all possible solutions) if the solution exists. But some kinematics problems don’t have any solution if the target for the end-effector is inaccessible. Iterative methods offer a general solution of inverse kinematics. Their disadvantage is that they converge to only one solution even if there exists more or they find a closest solution if it doesn’t exist.

Geometric methods use the knowledge of the manipulator geometry. This method has a disadvantage that solutions for one manipulator cannot be used for a manipulator with different geometry.

To solve inverse kinematics with algebraic methods we need to solve equations for N degrees of freedom. Every joint holds transformation Mi that consists of a translation and rotation, both relative to his parents. So if we have a vector of parameters (transformations Mi) in joints q, the forward kinematics solution is the position and orientation of end-effector x by transformation composition

x = f(q) (5)

But for inverse kinematics solution we know the position and orientation of end-effector x and we need to compute the state vector q that is the inverse function to (5)

x = f –1(x) (6)

The solution of (6) is not simple. Function f is not linear, there exist one-valued function for (5) but for (6) there are more solutions q for one x. Algebraic solution would be to find all final solutions for (6) but nevertheless a such solution can be derived only for a specific manipulators. Therefore inverse kinematics is solved with iterative methods.

Iterative solution is based either on matrix inversion or on any form of optimization. Matrix inversion is a complex process that is not only computational difficult but offers other problems that come from their numerical instability. Optimization methods bypass the problem of matrix inversion. These methods minimize the error in kinematics chain. Iterative approach is based on continuous closing to solution for every joint in a chain. In general these methods are more inaccurate and they converge only to one solution. But these methods are suitable and fair enough for kinematics simulation.

We studied and implemented three methods for inverse kinematics. All methods are iterative. The first method uses vector algebra to solve IK task. The method goes through the whole chain from the end-effector to the base and sets the corresponding joint values based on the force vector. This is repeated until an acceptable solution is found. The second method, transposition of Jacobi matrix [5] bypasses the matrix inversion problem with help of minimization. The third method, Cyclic Coordinate Descent (CCD [5]) is an iterative method based on position and orientation error function.

2.4 Summary

This section discussed the main problem areas of human body kinematics modeling. As a human body representation we have chosen a skeleton. All transformations on a human body are reduced to transformations on the skeleton. For rotation computation we introduced two methods. The Rodriguez rotation matrix is used for rotation computation. The quaternions are used for joint state representation because of their mentioned advantages (rotation composition and backward transformation). For inverse kinematics problem we introduced three methods of getting solution. Only iterative methods present optimal solutions. Algebraic methods provide solutions only for a small kinematics chains with a maximum of 6 DOF, which is not enough for a human body simulation. Geometric methods exist only for a special set of kinematics manipulator. Therefore we introduced three iterative methods for inverse kinematics tasks. The speed, which they find a solution with, depends on the number of DOF in selected kinematics chain, on the desired precision and on the target distance. All three methods provide an acceptable interactive solution by a precision of 0.01 to 0.0001. These precision values are acceptable for human body simulation. All three algorithms can be improved for a better real movement reflection. The speed of algorithms is naturally influenced by a precision and also by sensitivity. The smaller the sensitivity the faster the solution. Sensitivity also influences the nature of human body movement. As a summary of the three methods we can say that the simple and CCD methods are better because of their immediate change. The Jacobi method changes the chain after it went through the whole chain. But all in all, all three methods are suitable for interactive inverse kinematics solution.

3. Experimental Tool for Kinematics Simulation

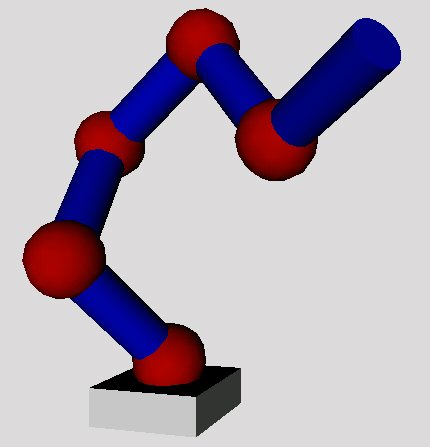

For experimenting and evaluation of the above mentioned methods and algorithms we developed a simple application. The program enables interactive human body modeling based on user input. User has the possibility with help of forward or inverse kinematics to set an arbitrary body pose. By manipulating the model with help of inverse kinematics has the user opportunity to select from the three iterative methods. Application also enables the possibility to create human body keyframed animation with various interpolation algorithms. Application implement algorithms for solving presented areas of simulation of human body kinematics. Final application is designed and implemented in C++ on OpenGL platform in Windows 95 environment. The figure 3.1 shows application window with the human body model.

Figure 3.1: Experimental program for demonstrating human body kinematics

4. Kinematics Modeling and VRML

For our experimental implementation environment we decided to choose the internet platform- using standards like VRML and Java (JavaScript, respectively). The reasons are world wide support, hardware platform independency and upgrowing popularity and applicability[10]. We have experienced with partial problems: user interface (menu system), body model (joint and skeleton representation) and algorithms for inverse kinematics in choosen languages.

First we want to mention a inconsistent implementations of the VRML 97 standard (especially in error detection). For our experiments we decided to use following two software combinations: Microsoft Internet Explorer 5.0 with ParallelGraphics Cortona VRML Client 2.0 and Netscape Communicator 4.6 with Cosmo Player 2.1.1. Main differences were in the level of error messages. The behavior of both software combinations was very inconsistent and we spent lot of time to detect the source of the problem. We used Sun Java 1.2 for Java parts of code.

4.1 User Interface- Building a Menu

User interface in 3D world is a bit new practise for users growed up in desktop-like applications. As a useful and user-friendly user interface (at least in the beginning of 3D navigation) we decided to create a 3D menu system.

There are some possibilities how to do a menu: popup lists outside the 3D view (the same technique as in usual desktop applications), symbolic tools placed around the avatar or some popup list as a part of 3D view. We decided for the last one.

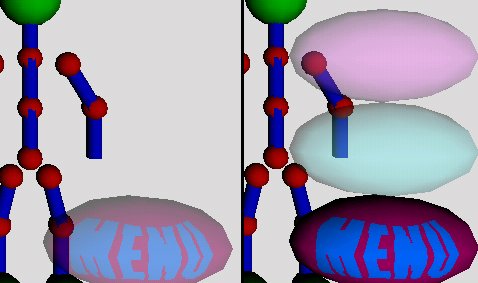

We tried to use different menu items geometries and then selected ellipsoids for represention a root and items of the menu. To distinguish different items of menu we used colors and bitmap images. To do the unused menu item most invisible we used color transparency as shows Figure 5.1. This idea is similar to that of Apple Macintosh "Aqua" [11].

Figure 5.1: Inactive and active menu.

4.2 Simulating Joints in VRML

There are two alternatives how to model simple joint in VRML 97: SphereSensor and a set of CylinderSensors.

The first one does not allow simple constrains modeling. This joint model consist of a Sphere and SphereSensor. The behavior of such an implementation is user-friendly but adding a constrains for this type of model requires a lot of Java code resulting in slower interaction. Example of sphere joints and sensors is shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2. Simple Sphere joint hierarchy.

The second case is a set of CylinderSensors, adding a constrains and a bit of complexity (for every degree of freedom there has to be a separate sensor). This results in a less user-friendly interface but supports very useful (not any time it is required) angle constrains. In this model we used different color for every axis of rotation and color transparency, too. Example of cylinder sensor is shown in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3: Complex Cylinder joint hierarchy.

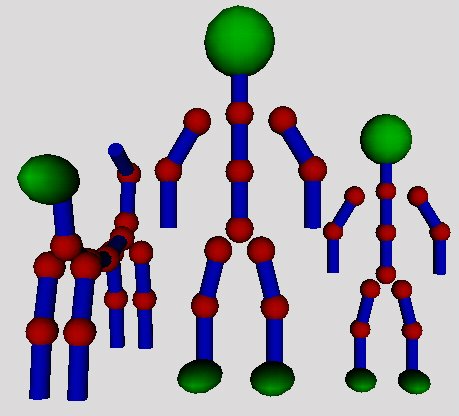

4.3 VRML Skeleton

We have created a human body as a hierarchic model of joints and bones with the equal size. Figure 5.4 shows two human skeletons ("parent" and a "child") with their chronic best friend.

Figure 5.4: Skeleton family with dog.

The animation performance of such a representation is very good, the problem is unrealistic modeling behaivior because of nonexistence of any joint constrains (in this model).

Figure 4.5: Complex human joint model [12].

4.4 Inverse Kinematics

In the field of inverse kinematics we have implemented just algorithms for tree- navigation in VRML. We have prepared algorithms for distributing kinematics information through the tree of nodes to get the inverse kinematics algorithms work. The problem with VRML modeling world is in the positioning system- VRML uses local positions and most of inverse kinematics algorithms require global positions.

There are two alternatives for solving this- keep the global position in every joint and distribute relative changes or set the local position in every single step. Actually we are working on these solutions.

5. Conclusions and Future Plans

In the area of Human Skeleton Modeling we have introduced basic problems like human body representation and kinematics. We have chosen a simplified model – skeleton as human body representation. Then we have discussed forward and inverse kinematics methods. All the methods and techniques were implemented in an experimental application.

In the Kinematics Modelling in VRML we have introduced few techniques important to model a human animation. We have created a background for future implementation of a full-VRML application (with parts of Java code) to introduce human animation on the platform of Internet.

We discussed menu system implementation, kinematics model of joint (in two alternatives) and implementation of inverse kinematics algorithms for VRML. Our future plan is to create a complex joint model, including the advantages of both subscribed models, to create a complete menu navigation system and finally implement some of the inverse kinematics algorithms.

6. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank associate professor Martin Sperka, for his advices. We also would like SWH, s.r.o. Bratislava for their hardware and Internet support.

7. References

[1] Horniak, M.: Program for the Visual Simulation of Mimics when Speaking. Master Thesis. Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Slovak University of Technology, Bratislava, 1999.

[2] Sperka, M.: Telepresence and Human Body Modeling. Proceedings: Symposium on Telemedicine and teleeducation in Practice. In: Symposium Proceedings International Symposium on Telemedicine and Teleeducation in Practice. Kosice March 22-24, 2000, pp. 281 – 285.

[3]

Skala Vaclav: Nonlinear coordinates and their application in computer graphics, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of West Bohemia.[4] Kondo Koichi: Inverse kinematics of a human arm, Robotics laboratory, department of computer science, Stanford University, Stanford, USA.

[5] Welman Chris: Inverse kinematics and geometric constraints for articulated figure manipulation, Simon Fraser university, Canada, 1993, www.fas.sfu.ca.

[6] Kwan W. Chin: Animating human motion using inverse kinematics, Curtin University of technology, www.cs.curtin.edu.au.

[7] Shoemake Ken: Animating rotations with quaternion curves, SIGGRAPH’85, Volume 19, number 3, pages 245-256.

[8] Dam B. Erik, Koch Martin, Lillholm Martin: Quaternions, interpolation and animation, Technical report DIKU-TR9815, Department of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen, 1998.

[9] Eberly David: Quaternion algebra and calculus, Magic Software, www.magic-software.com.

[10] Bruce Eckel: Thinking in Java, www.BruceEckel.com

[11] Apple Macintosh: New OS X, "Aqua", www.apple.com

[12] Humanoid Animation Working Group, www.hanim.org

[13] Carey,R, Bell, G.: The Annotated VRML97 Reference Manual. ISBN: 0201419742, 1997